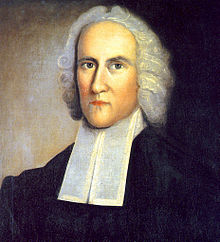

So we've seen over the past few weeks the historical and sociological factors that were affecting the community in which Edwards ministered. This week, we get down to the business of answering this question... Did Edwards invent Youth Ministry? Now, whilst Edwards held to the

traditional view of puritan New England which valued respect and deference to

elders and older members of society, Edwards also displayed a particularly

favourable view of youth.[1] He thought it difficult for those over fifty

to convert, and said it was better to trust God when young in order to grow up

into a deep habit of Godliness.[2] Edwards

himself was also relatively young when he began his ministry in Northampton,

only twenty-five years old, and so he was sympathetic to the youth in his

congregation and paid close attention to them in his preaching and pastoral

care. [3]

Differing from those such as Hooker

who ministered before him and had a relatively simple view of childhood, Edwards

recognised three distinct stages of childhood development, infancy (from birth

to age six or seven), childhood (from seven to fourteen to sixteen) and youth

(sixteen to twenty-five).[4] Edwards said, ‘The age of man is frequently

distinguished into childhood, youth, middle age, and old age.‘[5] He believed children reached a crucial turning

point around age seven, ‘in terms of their ability to reason and grasp abstract

concepts.’[6] Edwards ‘also shared the modern assumption

that children experienced another significant transformation during puberty –a

stage he identified as “youth” rather than “adolescence”.[7] Edwards ministry to children was one of the

most striking results of his theology of ‘religious affections which meant that

unlike earlier Puritan ministers, who equated religion with a rational

understand of Scripture, Edwards claimed that true faith was a matter of the

heart and that anyone, of any age was capable of demonstrating a changed heart

through changed behaviour.[8]

Due to his understanding of the

different ages and stages of children and youth, and his belief that true

religion was a matter of the ‘affections’ not primarily a rational thing, Edwards

attempted to tailor his religious instruction to fit the different and distinct

needs of each group.[9] Edwards wrote in a letter to Thomas Prince

that he had held special religious meetings for ‘children’ who were ‘under the

age of sixteen’ as well as for ‘young people’ between the ages of sixteen and

twenty-six.[10] Brekus notes that, ‘when Jonathan Edwards

began his pastorate in Northampton in 1727…he almost immediately began

directing his sermons to the children and older “youth” of the congregation.‘[11] In 1733, Edwards began to develop a technique

of preaching which involved a variety of tones of voice, and was directed

specifically to the adolescents in the community.[12] He also sought to explain the Bible in plain

language, so that younger people could understand.[13] Tracy

notes how Edwards continued to speak directly to young people because he viewed

most of the older parents in his congregation to have failed to bring their

children up in the faith.[14]

Perhaps a key insight in to the way

Edwards responded to his social setting can be seen in the application given in

one sermon,

‘Another thing I would advise is

private religious meetings. If young

people, instead of meeting to gather to drink or to frolic, would meet from

time to time to read and to pray to God, and together to seek their salvation,

doubtless it would have a great tendency to more and more lead them to think of

it and to fix their minds on it. This

would be found a great help to them, and this is the best way they can help one

another.’[15]

It seems here that Edwards is

arguing for special meetings of youth and young people to grow in their

Christian character and knowledge and to turn away from worldly living. In fact over and over again in sermons

delivered specially to ‘youth’ Edwards speaks of the need to pursue God rather

than the evil of the world,

‘The time of youth is the best

time; the days of old age are evil days for any such design. Old age is a very disadvantageous time to

seek God, to set about seeking God and salvation in comparison of youth’[16]

Or again, ‘It is ordinarily a much

more easy thing to affect the mind of a sinner in youth than one who is old in

sin’.[17] And

again, ‘Make religion the business of your youth.’[18]

Edwards believed that the best time

someone could seek their salvation was when they were a ‘youth’ and so he

worked hard with the youth in his congregation.[19] He preached favourably concerning young

people who decided to have faith and live pious lives.[20]

Another less favourable view of

Edwards’s work with young people, would be not that of a pastor adapting to his

context in order to bring the gospel to a growing generation of adolescent

young people, but rather a pastor desperate to keep his job by winning the

support of the younger generation over and against the older members of the

Northampton church. Harry Stout quotes

Kenneth Minkema’s research that showed that a large majority of the members who

criticized Edwards and eventually dismissed him were older members who had

entered the church under the ministry of his predecessor, Solomon Stoddard. [21] Stout argues that, ‘In retaliation, he

[Edwards] berated the aged as too old for conversion and held the youth up as

role models of faith.’[22] Minkema goes even further arguing Edwards

developed an antagonism towards old persons that, ‘ultimately verged on

outright hostility’.[23] He also notes that Tracy has shown that

Edwards gained the allegiance of the town’s youth during the awakenings of

1734-35 and 1740-42, only to have them turn on him when he was dismissed in

1750.[24] This could be further evidence of a man

driven more by the need to survive. When Edwards was sacked he claimed, ‘that

many youths continued to support him, but the majority of his church denounced

him for his rigidity and harshness.’[25] So whilst Edwards did seem to rely on the

support of the youth it seems likely that his focus on the youth was because he

simply found them more willing or likely to convert, then because he was trying

to use them to keep his job secure.[26]

For many, Edward’s ‘youth ministry’

is seen as one of his most notable successes as a Pastor.[27] Ava Chamberlin notes,

‘The Northampton youth, those

young men and women between the ages of fifteen and twenty-six who were

preparing to make choices about career, marriage, and family formation, were

the group most affected by changing social and economic conditions. As with youth throughout New England, the

burden of growing land scarcity fell disproportionately on their shoulders, and

increasing the conflicts and anxieties of adolescence.’[28]

In fact it was the youth became the

main participants in the revivals in Northampton, for which Edwards is largely

remembered, in 1734-35 and again in 1740.[29] Harry Stout notes that Edwards would often

strategize for revival and that youth and young people were always at the

centre of his thoughts and plans.[30]

[4] Brekus, ‘Children of Wrath, Children of Grace: Jonathan Edwards and the

Puritan Culture of Child Rearing’, 302.

[5] Cited in, Brekus, ‘Children of Wrath, Children of Grace: Jonathan Edwards and the

Puritan Culture of Child Rearing’, 302.

[6] Brekus, ‘Children of Wrath, Children of Grace: Jonathan Edwards and the

Puritan Culture of Child Rearing’, 302.

[7] Brekus, ‘Children of Wrath, Children of Grace: Jonathan Edwards and the

Puritan Culture of Child Rearing’, 303.

[8] Brekus, ‘Children of Wrath, Children of Grace: Jonathan Edwards and the

Puritan Culture of Child Rearing’, 318.

[9] Brekus, ‘Children of Wrath, Children of Grace: Jonathan Edwards and the

Puritan Culture of Child Rearing’, 303.

[10] Brekus, ‘Children of Wrath, Children of Grace: Jonathan Edwards and the

Puritan Culture of Child Rearing’, 302.

[11] Brekus, ‘Children of Wrath, Children of Grace: Jonathan Edwards and the

Puritan Culture of Child Rearing’, 302.

[12] Tracy, Jonathan Edwards, Pastor: Religion and Society in Eighteenth

Century Northampton, 77–78.

[13] Brekus, ‘Children of Wrath, Children of Grace: Jonathan Edwards and the

Puritan Culture of Child Rearing’, 303.

[14] Tracy, Jonathan Edwards, Pastor: Religion and Society in Eighteenth

Century Northampton, 77–78.

[15] Jonathan Edwards, To the Rising Generation: Addresses given to

Children and Young Adults (Orlando, Fla: Soli Deo Gloria Publications,

2005), 25.

[21] Harry S. Stout, ‘Edwards as Revivalist’, in The Cambridge Companion

to Jonathan Edwards (ed. Stephen J. Stein; Cambridge companions to

religion; Cambridge ; Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 137.

[23] Kenneth P. Minkema, ‘Old age and religion in the writings and life of

Jonathan Edwards’, Church History 70/4 (2001): 675.

[25] Brekus, ‘Children of Wrath, Children of Grace: Jonathan Edwards and the

Puritan Culture of Child Rearing’, 323.

[26] Edwards frequently wrote about the many children and young people who

were converting during his ministry. See Stout, ‘Edwards as Revivalist’, 137.

0 comments:

Post a Comment