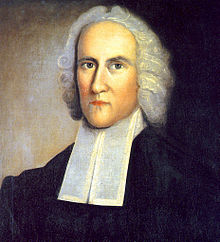

Last week we saw the context in which directly preceded the work of Edwards. This week we'll look at what was happening when he began his work in his church in Northampton. By the time Jonathan Edwards began

his work in Northampton in the late 1720s there were numerous changes occurring

to the social structures of Puritan religious, family and economic life. The first major shift was that of the

parent-child relationship. Brekus notes

that the power parents had over their children began to weaken significantly in

the eighteenth century due to a variety of sociological and other cultural

forces and Edwards observed much disrespect by youth for their parents and a

lack of control of youth by their parents.[1]

One of these cultural forces was a major

issue of land ownership, which was occurring during Edwards’s time at

Northampton.[2] In previous generations land was given to

young men as they came of age so they could start their own families. However, land was now becoming scarce, and

land had to be either purchased or inherited.

Failing this, the purchase or inheritance of land, young men would have

to move to a different town or out to the frontier. Ava Chamberlin notes that previously, the

giving on land to a young man was part of his ‘coming of age’ and so the lack

of land led to a prolonged ‘adolescence’ among young people who could not go

through the rites of passage of land ownership, marriage and family creation. [3] The average age of marriage rose to 28.6

years and a distinctive youth culture began to emerge.[4] This culture was, ‘marked by rebellious and

socially unacceptable behaviour’ and Edwards noted, at the beginning of his

pastorate in Northampton, that the youth were, ‘very much addicted to night

walking, and frequenting the tavern, and lewd practices’.[5] This evidence contradicts a prevailing view

outlined previously amongst youth ministry specialists that adolescence began

in the 18th Century and therefore there was no youth ministry prior

to this.[6] Patricia Tracy adds to the work of

Chamberlin and shows that there was a ‘crisis of adolescence’ in the 1730s and

1740s that contributed to the success of the Northampton revivals. [7]

‘It was at this time in much of

New England that young people first had to confront the necessity of making a

choice about what vocation to follow, or even what town to live in, for the

rest of their lives. Socioeconomic

change was cutting them off from the moorings of traditional concepts of work

and community life, and Calvinist doctrines [that Edwards preached] may have

eased the tension of facing a new world.’[8]

So it is clear that Edwards

ministered in a time of fairly rapid change.

Tracy notes that the,

‘Changing circumstances of

practical life were bringing young men more and more into conflict with their

fathers. Their “wild” behaviour, as

commented upon by Edwards and others, signified both their own assertions of

independence and the difficulties that their parents were having in asserting

and enforcing their own authority. When

the advice that an older generation could give no longer seemed to fit present

social realities, and when parents could no longer use economic rewards to

govern their children, there was indeed a decline in traditional family

government.’[9]

It is into this decline of family

government, and growing sense of ‘adolescent’ crisis that Edwards began to

adapt his theological views of youth and children and the way he did ministry

with and to them, and it is to Edward’s response and thought that we now turn.

[1] Brekus, ‘Children of Wrath, Children of Grace: Jonathan Edwards and the

Puritan Culture of Child Rearing’, 308.

[2] Ava Chamberlain, ‘Edwards and Social Issues’, in The Cambridge

companion to Jonathan Edwards (ed. Stephen J. Stein; Cambridge companions

to religion; Cambridge ; Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 330.

[6] Chap Clark and Mark Cannister both argue that adolescence is a recent

social phenomenon. However simply because it has only being recently described

and explained by sociologists does not mean that it did not exist in historical

contexts prior to its definition. In fact it is likely that sociologists did

not begin to describe the phenomenon until it was well established. If we are

able to trace the key features of “adolescence” to Edwards’s day as Chamberlin and

Tracy do, then we can show that youth ministry was practiced in that time. Chap

Clark, ‘The Changing Face of Adolescence: A Theological View of Human

Development’, in Starting Right: Thinking Theologically about Youth Ministry

(ed. Kenda Creasy Dean, Chap Clark, and Dave Rahn; Grand Rapids, Mich:

Zondervan/Youth Specialities Academic, 2001), 44–45; Cannister, ‘Youth Ministry’s

Historical Context: The Education and Evangelism of Young People’, 81.

[7] Patricia J. Tracy, Jonathan Edwards, Pastor: Religion and Society in

Eighteenth Century Northampton (American Century Series; New York: Hill and

Wang, 1980), 88.

0 comments:

Post a Comment